Current Book Project

Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals: A Fugitive History of Art and Science

In 1962, the American painter Mark Rothko donated five wall-sized paintings to Harvard University that he created for a penthouse dining room in the newly constructed Holyoke Center near Harvard Square. Soon after installation, the paintings faded from exposure to sunlight and were damaged by neglect. For decades, conservators tried to diagnose what made the paintings deteriorate and how to restore the “fugitive” color they deemed essential for their legibility.

In 2014, a technological restoration of the paintings was completed and exhibited at the Harvard Art Museums. Color-compensating images were projected onto the paintings’ surfaces to restore their original appearance. By turning the projectors off for one hour before the exhibit closed each day, the Museum dramatized the artwork’s before-and-after transformation. Visitors were invited to decide for themselves whether the experimental procedure successfully restored the Murals’ “inner light.” The spectacle also gave the exhibition a haunting mood that sparked debate about the authenticity of the remediated artwork.

While Harvard’s intervention restored the paintings’ colors, it also proved to be a misrecognition of Rothko’s larger enterprise as a painter. I document how Rothko made his theatrical paintings to destabilize the modern ways of knowing that Harvard’s conservators and curators upheld.

Rothko’s images present a visual aporia that directs a spectator’s attention toward the artwork’s presence as a moral and rhetorical act of disappearance. Seeing thus becomes an aspect of staging a conceptual paradox designed to evoke a unitary feeling that Rothko associated with pre-Socratic forms of myth and religious experience.

My book project is a microhistory of a single work of art located at one of America’s most culturally influential academic institutions. Across six decades, I retrace the biography of the Harvard Murals while analyzing their aesthetic, epistemological, and phenomenological transformation. I describe how Rothko made his paintings to perform as an aporetic experience, and how that experience was converted into a project of scientific scrutiny.

The artwork’s negative identity was made positive in performative acts of semblance that stimulated new interest in its technological revitalization, while yielding ambivalent feelings about Rothko’s ghostly presence in the theatrical display. The Murals are now inseparable from Harvard’s use of them to authorize a vision of the future where Rothko’s art becomes a stage for the epistemic reproduction of his work’s most contradictory and elusive qualities.

Seeing a Rothko for the first time in 1962 (clip from an episode of Mad Men).

Seeing the Rothkos restored with light (video from the Harvard Art Museums).

Recent Research on Digital Reproduction in Cultural Heritage

I contributed an essay titled “Verum Factum Arte: Scanning Seti and the Afterlife of a Pharaonic Tomb” to an edited volume titled The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality.

My essay offers a new analysis of the work of Factum Arte by looking at their long-term effort to digitally scan and materially reproduce the tomb of the Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh, Seti I. I describe how the studio is pursuing a new professional standard for preservation in cultural heritage that mingles data-driven objectivity with aesthetic experimentation. Factum Arte privileges the artisanal act of re-making as the source of an artifact's originality, and positions the reproduction as a continuation of the artifact’s material aura. The whole of an original is the sum total of its copies. I argue that Factum Arte’s facsimiles and exhibitions perform in a way that reveals a connected history of constructivist practice art and science, which is expanding the role of conservation scientists as direct interpreters of historical meaning for museum audiences.

Archaeological Semblance and the Remaking of Roman Pottery Practice

Marzuolo Archaeology Project, Cinigiano, Italy, 2017.

For my masters thesis in cultural anthropology, I conducted fieldwork with the Marzuolo Archaeology Project (MAP), a multi-year excavation of a rural Roman craft production complex dating to the first century CE. The project's principal investigators have been working at the site to uncover evidence of early experimental pottery-making practices that challenge archaeological assumptions about terra sigillata—a ubiquitous form of mass-produced pottery which is used to shape knowledge about the Roman economy. The very notion of “economy” in our modern sense is something that MAP’s investigators challenge through their reconceptualization of what it means to innovate a craft in the rural time and space of a community that left evidence of experiences which exceed any simplified understanding of Roman life.

Through an ethnographic analysis of the dig, my thesis demonstrates how MAP's investigators are using concepts drawn from science and technology studies to revise historical narratives about Roman pottery and its production. I also address an essential, yet overlooked aspect of archaeological excavation — aesthetic appearing. Functioning like a theatrical stage, the archaeological site is shaped by semblance, metaphor, conceptual blending, and cognitive compressions of time and space. This proved to be especially relevant in combination with MAP’s methodologies that focus on both human and non-human materialist agencies. Sensory and emotional scenarios are used to shape different realities and to revise historical knowledge.

Seeing Sonic Atmospheres:

GIS as a Tool for the Reenactment of Archival Sound

Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, 2016.

In 2013, I began to conduct research on an archaeoacoustic event that took place in Ansacq, France in 1730. The archival record of the occurrence was recently rediscovered by music theorist Brian Kane, who describes it in Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound In Theory and Practice. I was intrigued by the performative aspects of this event, as well as the conundrums that it creates for historical representation.

Along with an article-length historical essay about the event, I also produced a ten-channel sound installation with composer John Berendzen, and a series of drawings that visually re-imagine the event (inspired by the photographs of Axel Hoedt).

Most recently, I simulated the event by using GIS software to visualize historical sound data as a geospatial representation.

In the spring of 2016, I presented my simulation at the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society (IBES) as part of their Atmospheres Conference. The video below summarizes my research and the simulation. Viewing in HD with headphones is best.

Presentations

Atmospheres (Earth, Itself 2016 Conference) - Institute at Brown for Environment and Society (IBES), Brown University

Reanimating Phenomenal Others:

How to Bring Museum Objects Back to Life

At Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, 2015.

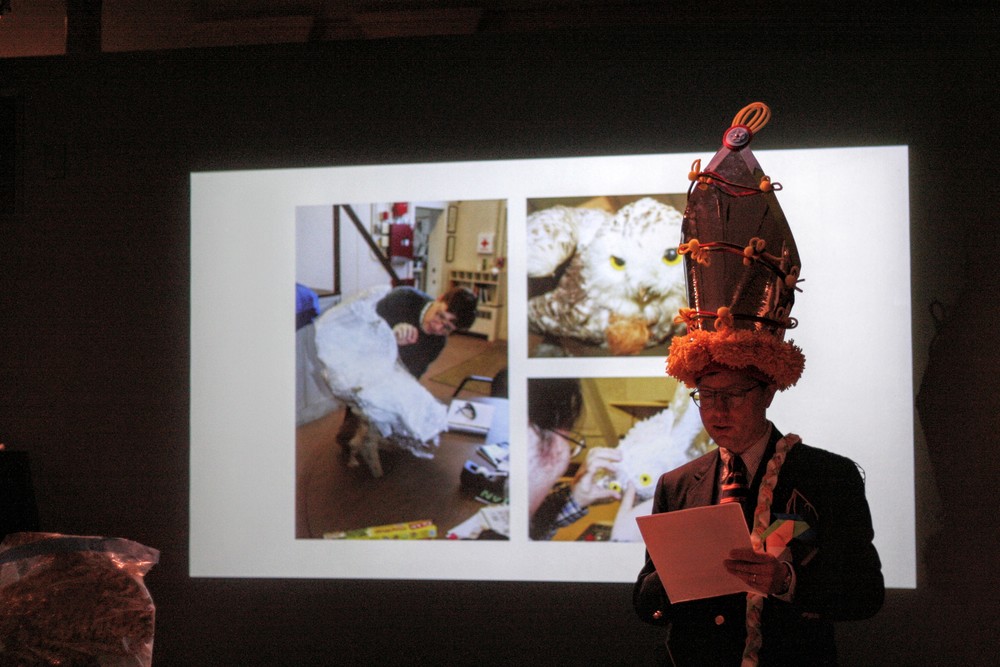

Are museum methods for collecting phenomenal forms of otherness missing the point? What is lost when objects of wonder and magic are put into hibernation on museum shelves? Anthropologist Emily Avera and I wanted to find out. In collaboration with the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology and a group of ten students at Brown, we created a performance-based research project that brought archival objects back into the world by re-making them as replicas.

In response to the Symposium’s theme of museological loss, we searched the Haffenreffer for objects that were unknown, or open to speculation. For example, we studied a Baoulé mouse oracle from the Côte d’Ivoire, a phrygian cap from the French Revolution, and a dilapidated owl found in the museum's attic. Our research included video walks among the collections, sketches and photos, literature related to the objects, and even XRF spectroscopy scanning. In the design studio, we worked together to make replicas, or “surrogates” of the objects that we could interact with beyond the museum’s walls.

By making surrogates, we were able to adapt the objects, manipulate their qualities and forms, and find ways to reinterpret their meaning in relation to our lives in the present. The surrogates took on a number of forms, from paper maquettes and illustrations, to songs and scenarios performed around campus and the city. This unusual approach allowed us to address myriad historical and ethical questions that govern the care of museum collections, while giving the objects themselves new experiences in life.

Presentations

Lost Museums Symposium - Brown University

To Search - RISD Museum

AAA 2015 Annual Conference - Denver, CO